<View of southern Ivanpah Valley from the Clark Mountain foothills in Mojave National Preserve. On a December 2009 site visit we found Desert bighorn sheep tracks and scat on this ridge full of Catclaw acacias, Buckhorn cholla, and Mojave yuccas, leading down to a small spring in the canyon below, where a single cottonwood tree was turning yellow (distant center).

Biological Resources

The Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System (ISEGS) project in eastern San Bernardino County, California, would have major impacts to the biological resources of the Ivanpah Valley, substantially affecting many sensitive plant and wildlife species and eliminating a broad expanse of relatively undisturbed Mojave Desert habitat. Approximately 4,073 acres of occupied desert tortoise habitat would be permanently lost and many tortoises would need to be translocated west of the project site.

This was the conclusion reached by the California Energy Commission (CEC) in their Final Staff Assessment (FSA), the state agency that is charged with licensing large power plants, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the federal agency managing the site land in their parallel Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS). BLM will come out with a Final EIS in early 2010, but the Energy Commission is trying to quickly wrap up their decision.

Despite the tremendous problems associated with this project, it is given a green light to go ahead.

Rare Plants

^Butterfly bush (Buddleja utahensis), found on the small limestone hill next to Ivanpah 3.

Energy Commission staff consider impacts to five rare plants: Mojave milkweed (Asclepias nyctaginifolia), Desert pincushion (Coryphantha chlorantha), Nine-awned pappus grass (Enneapogon desvauxii), Parish’s club-cholla (Grusonia parishii), and Rusby’s desert-mallow (Sphaeralcea rusbyi var. eremicola) to be significant according to California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) guidelines because the project would eliminate a substantial portion of their documented occurrences in the state.

"Given the project’s location on a large portion of the Ivanpah Valley, and in particular, the bajada and alluvial fans that support special- status plant species, it is reasonable to conclude that a substantial portion of the suitable habitat for these plants would be affected by construction of the ISEGS project, increasing the threat of local extirpation of the Ivanpah Valley proportion of these species’ ranges" (page 6.2-71).

Rusby's desert-mallow is considered by the California Native Plant Society to be especially of concern, and is on its List 1B - Rare, threatened, or endangered in California and elsewhere. Rusby’s Desert-Mallow is a California endemic perennial herb; it is documented globally from less than 30 occurrences in Inyo and San Bernardino Counties in the Death Valley Region and eastern Mojave Desert in the Clark Mountain Range. It has a California Natural Diversity Database state rank of S2 (imperiled). It occurs in the Clark Mountain Range at Ivanpah Springs, on desert slopes and gravelly sandy washes and often in carbonate and limestone substrate, extending into the project area. This plant is also a BLM-sensitive plant species detected on site. This species was not detected during the 2007 surveys, but in 2008 15 individuals were mapped in 12 locations in Mojave creosote bush scrub within Ivanpah 1, 2, and 3, the construction logistics area, and the utility corridor.

Mojave Milkweed is limited to a very small area in eastern San Bernardino County. Currently, it is known from less than 25 occurrences, 16 of which occur in Ivanpah Valley in the project area. Its distribution outside of Ivanpah Valley is limited to a few very

old historic collections and only two other populations that have been confirmed extant. This plant also occurs in Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada but it has a California state rank of S1 (critically imperiled and vulnerable to extirpation from the state due to extreme rarity).

Other rare plants are somewhat more widespread, but taking into account the cumulative impacts of the dozens of other large utility-scale solar applications pending in the desert, this is little comfort: Small-Flowered Androstephium (Androstephium brevifloru), Utah Vine Milkweed (Cynanchum utahense), and Desert portulaca (Portulaca halimoides).

The California Native Plant Society noted that plant surveys were not carried out in for summer-rain germinating species, and thus several plant types may have been missed or under-represented.

The Energy Commission proposed avoidance and minimization measures that they claim could reduce impacts to three of these species (desert pincushion, nine-awned pappus grass, and Parish’s club-cholla) to less-than-significant levels. But impacts to Mojave milkweed and Rusby’s desert-mallow would remain significant.

The California Native Plant Society further commented that the project would eliminate

several square miles of occupied rare plant habitat. "There are no known techniques to mitigate for the loss of rare plants and their habitat in desert environments. Avoidance is the only mitigation that is appropriate for this site. There is no known method to compensate for the loss of this rare plant habitat. Simple habitat acquisition for the desert tortoise cannot provide adequate compensation for the loss of this high quality rare plant habitat. To be able to find comparable compensation habitat for the rare plants will require an enormous amount of fieldwork to survey private lands that might be occupied. Simple translocation of the adult plants does not perpetuate population structures for long term productivity and is an unproven mitigation for habitat

destruction. The scale of destruction of subsurface ecosystem components and seed

banks is impossible to mitigate....Currently, there are no known mitigation actions

that are successful for desert plants and habitats. The only legitimate option is, no

approval at this location. If approved for this location, a land compensation ratio should

be at least 5:1, especially in light of the massive push for energy development in the

desert and the projected cumulative effect generated from similar projects" (page 6.2-77-78). The Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife, and National Parks Conservation Association also recommended 5:1. But the Energy Commission went with a 3:1 land aquisition mitigation, but it may actually be 2:1 with the other third as cash for land management.

The California Native Plant Society continues: "There is only a short mention of one individual cataloging a single element from the site during the late summer. This is a critical failure for the complete analysis of effects to the environment from the proposed action. The region is poorly known botanically and therefore the failure to conduct summer/fall surveys prevents the ability to conduct a valid and complete analysis of effects of the proposed action. The revelation of the number of sensitive plants on site is an example of the poor understanding of the distribution of the flora for that region. Oenothera cavernae [not on the pre-survey list] was only recently discovered to occur in eastern California and there are most likely several other species yet to be documented. The presumption that a complete species account can be accomplished from previous years ‘skeletal’ remains fails to comprehend the ecological properties of native annual plants. The vast majority of native annual plant species disarticulate from the growing location after seed set and blow away and thus would be undetectable using the survey method used with this project. All of the surveys for annual plants were conducted in April 2008 subsequent to summer 2007 precipitation. [spring 2007 survey dates were not easily detected in the technical document]" (pages 6.2-78-79).

CEC/BLM agree with these comments, but gives only weak mitigation measures to try to deal with the problems.

In addition, the FSA/DEIS fails to identify and analyze the loss of carbon sequestration from plants and soils on the site that will occur under the proposed project.

>Green stems of Trumpet buckwheat (Eriogonum inlfatum).

The Energy Commission considered several mitigation measures, but rejected them. Buying land with populations of the rare plants was rejected because no private parcels with such species were found.

"Energy Commission staff investigated the possibility of off-setting project losses by placing land use restrictions on or enhancing BLM lands which contained one or more of these special-status plants and which were not currently protected as part of the Mojave Preserve or within a Desert Wildlife Management Area (DWMA). However, such a proposed action (land use changes potentially affecting other uses of the land) would trigger a requirement for a separate NEPA analysis. Consequently, this mitigation option would not be timely for this project as it would take considerable time and effort before it was even determined whether such an option was feasible" (page 6.2-40).

Transplantation was brought up, but a studies have found that, even under optimum conditions, transplantation was not effective in 85 percent of cases. The California Native Plant Society has an official policy opposing transplantation.

So the Energy Commission came up with a "Recommended Conceptual Avoidance Approach." Reconfiguration of the project footprint within areas that support the highest density and diversity of special-status plants could "substantially reduce impacts to special-status plant species." "To the extent feasible the project owner shall avoid and minimize disturbance to all special-status plant species within the project site," the Energy Commission adds. The project footprint has expanded twice since the application was submitted. The most recent expansion was 365 acres, from 3,700 to 4,065 acres, a result of the applicant proposing the addition of stormwater detention ponds. These ponds have since been eliminated from the applicant’s proposal without any adjustment downward in the project area. "Energy Commission staff has therefore assumed that the 365 acres gained when the ponds were eliminated could be applied to protecting special-status plants rather than expanding the number of heliostats in the northernmost portion of ISEGS 3 and ISEGS 1, areas that support many special-status plants" (page 6.2-41). But because of this precise geometric configuration needed for the heliostat feild, we doubt BrightSource will agree to this.

The recommended mitigation approach is to protect at least 75% of the individuals of

each of the five special-status plant species within the project area. But even CEC and BLM admit that this level of protection may not be possible for Rusby’s desert-mallow and Mojave milkweed because of the scattered distribution of these species in the project area (page 6.2-42).

"The impacts to Mojave milkweed cannot be sufficiently reduced by avoidance in the three areas described above because it is so widely distributed throughout the site. The impacts to Rusby’s desert- mallow would also remain significant in a CEQA context because construction would still eliminate a substantial portion of its global population even if the majority of individuals are protected on site" (page 6.2-44).

Even if avoidance for any rare plants could be achieved, this plan still allows the habitat of these species to be carved up and fragmented, creating islands of habitat isolated from other populations and potentially even pollinators due to the heat created by the project's sun-reflecting and concentrating design. This does not provide adequate minimization to the severe impacts to these populations.

^Silver cholla (Cylindropuntia echinocarpa) flowers in spring.

Weeds

The FSA/DEIS admits: "Non-native forms may be introduced or existing weeds spread due to construction and operation of ISEGS. Many invasive non-native species are adapted to and promoted by soil disturbance, and seeds are commonly transported on vehicles and by wind and water. Exotics can out-compete native species because of minimal water requirements, high germination potential and high seed production...and can become locally dominant, representing a serious threat to native desert ecosystems.... The ISEGS project could adversely affect special-status plant occurrences near the project area by the increase and spread of non-native plant species. Soil disturbance from construction activity often renders habitat vulnerable to invasion by non-native species" (pages 6.2-63-64).

The California Native Plant Society writes: "The species lists and site evaluation clearly highlights the proposed project location as pristine and ecologically rich. The number of rare plant species and abundances as well as several rare animal species identifies this site as warranting protection not destruction. This site is not degraded. Only a very few non-native troublesome weeds at low densities from the location, and the vast size of the disturbance from the proposed project will undoubtedly cause a serious invasion problem for the area. If the project is approved there must be a guaranteed bond of a sufficient amount to pay for the ongoing [life of the project and beyond] weed management the project will create" (page 6.2-79).

The FSA/DEIS states that mowing of vegetation and mirror washing will likely promote the proliferation of non-native invasive weeds, in particular cheat grass and red brome, two species of particular concern at the project site. The Energy Commission require all weed growth brought on by mirror washing be controlled by trimming the weeds to less than six inches in height.

The FSA/DEIS states that mowing of vegetation and mirror washing will likely promote the proliferation of non-native invasive weeds, in particular cheat grass and red brome, two species of particular concern at the project site. The Energy Commission require all weed growth brought on by mirror washing be controlled by trimming the weeds to less than six inches in height.

Any native succulents or plant species of concern within the drainage area of mirror washing will be monitored quarterly, the Energy Commission states. If wilting or other signs of stress occur, the plants would be moved to an unshaded portion of the operations area. This seems to us to create even more unnecessary soil disturbance.

<Red brome (Bromus madritensis ssp. rubens) taking over.

The FSA/DEIS says: "Cheat grass, red brome, and Mediterranean grass are already present in the project area and are expected to increase as a result of construction- and operation-related disturbance. The proliferation of non-native annual grasses such as these have dramatically increased the fuel load and frequency of fire in many desert ecosystems" (page 6.2-34).

"Other indirect effects on plant communities during operation include soil compaction,

changes to the soil structure by use of dust suppressants, and changes in the

distribution of precipitation falling on the solar fields" (page 6.2-34).

Sahara mustard (Brassica tournefortii) was found at two

Sahara mustard (Brassica tournefortii) was found at two

locations, in Ivanpah 3 and in the utility corridor. This species is of high concern; Cal-

IPC has declared this plant highly invasive and recommends that it

should be eradicated whenever encountered.

>Sahara mustard dry stems clog habitats.

Other weed species that will most likely increase include: Cheat grass (Bromus tectorum), Mediterranean grass or Splitgrass (Schismus spp.), Russian thistle (Salsola sp.), London rocket (Sisymbrium irio), and Filaree (Erodium cicutarium).

Biological Soil Crusts

Soil biological crust is a mix of organisms that occupy and protect the surface of the soil in most desert ecosystems. The organisms often include filamentous and non-filamentous cyanobacteria, mosses, lichens, liverworts and fungi.

Damage to intact desert soils with biotic crusts and the resulting increased siltation during flooding and dust are not adequately analyzed in the FSA/DEIS. Biological crusts protect the soil and hold weeds at bay.

<Soil crust we photographed at the Ivanpah site. It is dry and dormant, but will become green with rains.

An ammendment to the FSA/DEIS adds: "Soil biological crust shall be preserved by collecting the

upper 1/4 inch of topsoil from areas to be graded. Applicant may flag specific areas

known to contain biological crust organisms or collect upper soil from the entire area. BLM or its designated representative must concur that the correct areas have been flagged if collections are to include less than the entire area over which the soil surface will be disturbed.

"Collections are to emphasize filamentous cyanobacteria; but other cyanobacteria, mosses, lichens, and liverworts are also considered valuable contributors to the soil biological crust and will be important in protecting against erosion and reducing weed invasion. Soil surface crust shall be air dried and stored... Soil biological crust shall be re-applied at the time of replanting by crumbling the stored material and broadcasting it on the surface of the soil. Stored crust material may be applied to an area up to 10 times the area from which it was collected. Approximately 10 percent of the stored material shall be broadcast on topsoil storage areas among plants being grown for seed and soil microorganisms. When the growing cycle progresses to new planting, the soil supporting biological crust shall be collected and stored by the same methods prescribed for collections from the original soil, in clearly labeled bags or other suitable containers" (pages 6.2-161-162).

We would like to know how biological crust could be stored, and where, for the 50 years of the project lifetime? No details are given. This seems highly unlikely to succeed.

Desert Tortoise

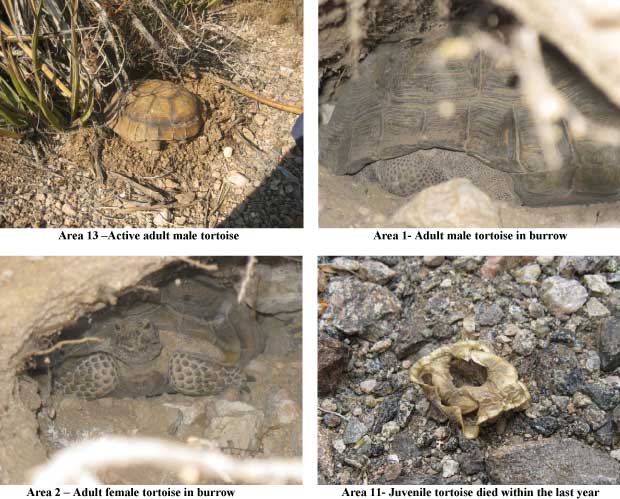

^Tortoises and sign found on the ISEGS site during 2008 surveys. (From: CH2M Hill. 2008. Supplemental Data Response Set 2D. Revised Draft Biological Assessment, pdf at www.energy.ca.gov >>here)

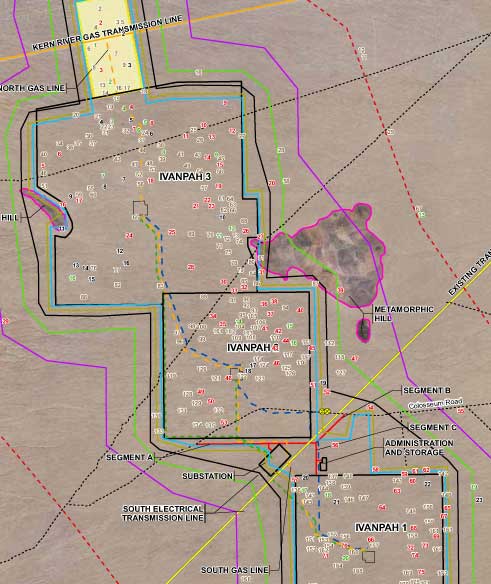

The proposed ISEGS project would be constructed within the Northeastern Mojave Recovery Unit, one of six designated evolutionarily significant units within the range of the Desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii). This population is genetically the most distinctive unit of the desert tortoise in the Mojave Desert. When the 1994 recovery plan was issued, some of the highest known tortoise densities were in southern Ivanpah Valley, with 200 to 250 adults per square mile (US Fish and Wildlife Service 1994, Desert Tortoise {Mojave Population} Recovery Plan. Portland Oregon). Densities for the northern Ivanpah Valley in the 1990s were typically less than 50 adults per square mile (ibid.).

Ivanpah Valley area is considered excellent quality tortoise habitat with some of the highest population densities in the East Mojave.

The FSA/DEIS states: "The project, combined with future proposed projects, would also significantly affect a genetically distinct subpopulation of desert tortoise within the

Northeastern Mojave Recovery Unit that occurs in the Ivanpah Valley..." (page 6.2-71).

The proposed project is located approximately five miles north of the Ivanpah Critical Habitat Unit for desert tortoise, just north of the I-15 and Route 164 (Nipton Road) interchange.

^Tortoise burrow in Ivanpah 3 site of the project proposal, October 2009. The fall was dry on this part of the valley, and tortoises were underground. Clark Mountain rises in the distance.

The 2007/2008 protocol desert tortoise surveys found 25 live desert tortoises, 97 desert

tortoise carcasses, 214 burrows, and 50 other tortoise sign. Tortoise sign and density was greatest in Ivanpah 1 at the southern boundary of the project site and was less dense as the survey moved towards the Clark Mountains and Ivanpah 3, according to the FSA/DEIS. On several October visits to the sites, we found numerous burrows on the northern part of the site, however.

>Map of the ISEGS site showing locations of tortoises, tortoise burrows, and carcasses found during 2008/2009 surveys. The area is dense with tortoise sign. (From: CH2M Hill. 2008. Supplemental Data Response Set 2D. Revised Draft Biological Assessment, pdf at www.energy.ca.gov >>here).

"The applicant has recommended impact avoidance and minimization measures to reduce these direct impacts to desert tortoise, including installation of exclusion fencing

to keep desert tortoise out of construction areas, relocating/translocating the resident desert tortoise from the ISEGS site, reducing construction traffic and speed limits to reduce the incidence of road kills and worker training programs" (FSA/DEIS page 6.2-48).

Recent translocations of tortoises at Ft. Irwin, California, however, failed and were halted, as coyotes began finding and killing large numbers of tortoises after they were moved to new locations. The California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) , US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, and Sierra Club expressed their concerns about the outcome of proposed desert tortoise translocations for the ISEGS project, and have requested that those concerns be addressed in any relocation/ translocation plans approved for the ISEGS project (page 6.2-49). The applicant surveyed potential tortoise relocation areas adjacent to the project site, and twice CDFG and USFWS requested more data as to the suitability of the habitat. CDFG still may have concerns, but the Energy Commission finally signed off on BrightSource's plan for moving tortoises to sections of the fan just to the west of the project.

^View of Clark Mountain and the ISEGS site below it (on the fan on the other side of the playa), as seen from Desert tortoise critical habitat in southern Ivanpah Valley, on the boundary of Mojave National Preserve. This foreground land is in the Ivanpah Desert Wildlife Management Area (DWMA). The project area is just outside it.

Mitigation for Tortoise

The FSA/DEIS states: "To fully offset impacts, the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) requires a full mitigation finding, which usually contemplates a mitigation ratio greater than 1:1 for compensation lands (i.e., acquisition or preservation of one acre of compensation lands for every acre lost). On past energy projects considered by the Energy Commission, the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) has required a 3:1 ratio to meet the CESA full mitigation standard for good quality habitat such as that found at the ISEGS" (page 6.2-53).

"Energy Commission staff’s proposed Condition of Certification BIO-17 specifies

compensatory mitigation for desert tortoise habitat loss at a 3:1 ratio, and BLM has

proposed nesting their 1:1 mitigation requirement within this framework. The Energy

Commission staff’s condition of certification requires a security for funding two-thirds of

their mitigation requirement. BLM would likely require the project owner to provide a

deposit to be held in a BLM-managed contributed funds account based on the area of

ground disturbance as determined by the final project footprint" (page 6.2-53).

"The BLM’s first priority for land acquisition would be private lands outside of the Mojave

Preserve that are within the Desert Wildlife Management Area (DWMA) portion of the

Eastern Mojave Recovery Unit. Remaining funds would be spent acquiring private lands

within the Mojave National Preserve and on additional management and enhancement

projects that would benefit the desert tortoise" (page 6.2-54).

"Energy Commission staff have concluded that the combination of the 2:1 compensatory

mitigation, as described in staff’s proposed Condition of Certification BIO-17, and the

BLM 1:1 mitigation described conceptually above, would meet CESA’s full mitigation

standard and would mitigate CEQA impacts to desert tortoise to less-than-significant

levels. Staff considers the combination of these two mitigation approaches to be a

complementary and complete mitigation package that would achieve 3:1 mitigation and

would satisfy state and federal requirements for mitigating impacts to desert tortoise" (page 6.2-55).

But fulfilling BLM’s 1:1 mitigation requirements might not include actually setting land aside, but rather actions such such as fencing and habitat restoration.

^Excellent tortoise habitat with creosote, bursage, pencil cactus, Mojave yucca, and galleta grass. Ivanpah 2 project site, with the large metamorphic hill in the mid-ground.

The compensatory mitigation plan for tortoises relies on so-called “nesting” to provide compensatory mitigation for loss of habitat and individuals for multiple plant and animal species. Because the plan described in the FSA/DEIS only addresses desert tortoise habitat, it may in fact be inadequate to provide for the mitigation needs of the many other species that will be impacted by the project. We believes that the Energy Commission and BLM must revisit this issue and explain how the so-called “nesting” of mitigation actually provides for compensatory mitigation for each species of rare or sensitive plant and animal, including listed species as well as Gila monster, burrowing owl, nesting bird species, badger, and Nelson bighorn sheep.

At the suggestion of the California Energy Commission, we submitted the following data requests on October 30th, 2009. The applicant objected to these requests due to issues with deadlines. The FSA/DEIS provides little information on the translocation site and survey protocol that was used to determine the feasibility of the site. We are concerned that the applicant did not follow protocol during the surveys of the translocation site. We feel that the following questions deserve an answer and that the applicant should be more cooperative about sharing this basic information. The below issues concerning the translocation plan remain unresolved in our view:

Data Requests:

1. Please submit copies of all desert tortoise pre-project survey data sheets.

2. Please submit resumes of Southern Nevada Environmental, Inc (SNEI) surveyors.

3. Please indicate the personnel that had a minimum of 60 days prior field experience searching for desert tortoises and tortoise sign.

4. For surveyors without 60 days prior field experience, provide a discussion of

how surveyors were trained and any measures that were taken to ensure they

obtained accurate survey results.

5. Please provide dates and times of tortoise surveys. If surveys were not conducted during appropriate seasons (April through May and September through October) as determined by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) April 2009 Pre-Project Field Survey Protocol (http://www.fws.gov/ventura/speciesinfo/protocols_guidelines/docs/dt/DT_Pre-project_SurveyProtocol_2009_FieldSeason.pdf), please explain the reasons. Was approval granted for any survey work conducted outside the spring and fall seasons by USFWS and California Department of Fish and Game (GDFG)?

6. If surveys were conducted outside recommended USFWS protocol seasons, please discuss how survey numbers would be as accurate as those obtained during optimal activity seasons.

7. Please provide temperature data collected during surveys. Were surveys conducted when air temperatures were above 40 degrees Celsius?

8. Please indicate whether any desert tortoises were handled during Project surveys. If tortoises were handled, please provide documentation of the section 10(a)(1)(A) permit(s) issued by the USFWS authorizing handling.

9. In the ISEGS Supplemental Data Response Set 2J, SNEI indicates that rainfall estimates were not obtained on site, but at higher elevations from Mountain Pass in different habitat, and approximately 50 miles away at Las Vegas. Please discuss how tortoise abundance estimates may be skewed by rainfall estimates that are not on site.

10. In the ISEGS Supplemental Data Response Set 2J, SNEI concludes that drought may be the prime cause for a possible decline in tortoises on the site. Please discuss why other potential causes for this decline were not discussed, such as disease, subsidized predation relating to the interstate highway, and livestock use.

From a document submitted by the contractor to BrightSource to the California Energy Commission, we learn the details of how the destruction of this desert habitat will begin:

"Prior to clearing vegetation and site grading, each site boundary would be permanently

fenced with an 8-foot-high chain-link for security purposes and permanent desert tortoise

exclusionary fencing would either be attached to the base of the security fence or installed outside the security fence to allow construction of linear facilities. Cattle grating would be installed to allow equipment access to the fenced sites and exclude desert tortoises. The first step would include clearing an approximate 10-foot-wide linear swath of vegetation along the entire outer edge of each facility boundary to create an internal perimeter road and install the fencing. The perimeter road would be within the fence line or site boundary. Once the fence is installed and prior to vegetation clearing and site grading, a desert tortoise clearance survey according to USFWS protocol and a project-specific translocation plan would be performed. Upon completion of the desert tortoise clearance survey and translocation, and prior to clearing and grading, the barrel cactus and Mojave yucca that would otherwise be removed or impacted during construction would be offered up for public salvage per BLM policy. These activities would be coordinated with the BLM" (From: CH2M Hill. 2008. Supplemental Data Response Set 2D. Revised Draft Biological Assessment, pdf at www.energy.ca.gov >>here).

A member of Basin and Range Watch (LMC) has worked on desert tortoise translocation projects in the Mojave Desert and can attest to how this works on the ground.

^A Desert tortoise missed by two clearance surveys on a large West Mojave construction project.

^Scraper-grader building roads in the West Mojave. Tortoises must be translocated, but avoidance of such habitat destruction is always preferable.

^Another tortoise missed by biologists, even after all burrows on the project site were excavated. There are more tortoises hiding usually than biologists can find, even after many months. West Mojave construction project of a similar size to ISEGS.

Gila Monster

"Gila monsters have the potential to occur in the ISEGS project area, particularly near

the metamorphic hill, immediately adjacent to the southeastern boundary of Ivanpah 3..." (6.2-28).

The FSA/DEIS states that the “compensatory mitigation plan, could offset the loss of habitat for this species and reduce the impact to less-than-significant” (page 6.2-47). The needs of the Gila monster may not be consistent with the needs of the tortoise. A separate mitigation plan should be developed for Gila monster, with separate mitigation land acquired if needed. The California Department of Fish and Game agreed that compensatory mitigation for Desert tortoise used to offset impacts to Gila monsters is inadequate.

The FSA/DEIS states that the “compensatory mitigation plan, could offset the loss of habitat for this species and reduce the impact to less-than-significant” (page 6.2-47). The needs of the Gila monster may not be consistent with the needs of the tortoise. A separate mitigation plan should be developed for Gila monster, with separate mitigation land acquired if needed. The California Department of Fish and Game agreed that compensatory mitigation for Desert tortoise used to offset impacts to Gila monsters is inadequate.

The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum cinctum) is a fossorial species that is very difficult to locate. The FSA/DEIS does not explain what kind of surveys were used to look for the species.

Dr. Daniel Beck of Central Washington University, who is the leading authority on the biology of helodermatid lizards had this to say about surveys last January:

“As you know it is extremely difficult to make accurate population estimates of Gila monsters, especially in the Mojave Desert, where they are even less frequently active than in the Sonoran Desert. Some sites in the eastern Mojave desert contain population densities of up to 20 lizards/square mile. I know of sites in southern Nevada that contain fairly high densities as well, perhaps as high as 10-15/square mile (just an estimate). High densities are associated with sites that have relatively high topographical complexity (lots of topographical relief, boulders, burrows, and potential shelters for Gila monsters). Sandy areas bordering rocky outcrops are good habitat areas. I'd advise decision makers not to assume the absence of Gila monsters based on short-term surveys” (personal communication 2009).

The BLM and CEC need to have qualified individuals do more complete surveys of the area for the species before any conclusions are made about population numbers. Populations of this species in the Mojave Desert are fringe populations and could carry unique genetic bottleneck traits that should be researched.

>We found this young inexperienced Sidewinder in an October 2009 visit, on the Ivanpah 1 lower site. It crawled into a rodent hole and rattled, which made us laugh because its head was down underground. It will be directly in line for graders to dig up its habitat if the project is licensed.

The FSA/DEIS admits: "Vegetation clearing and grading associated with ISEGS construction would directly affect wildlife by removal and crushing of shrubs and herbaceous vegetation, resulting in loss and fragmentation of cover, breeding and foraging habitat. Construction and operation of ISEGS could also result in wildlife being crushed, entombed in dens or burrows, and colliding with vehicles and power line conductors or towers. In addition, wildlife could experience increased predation levels from ravens and other predators attracted to the project site and could be disturbed by increased levels of noise and activity" (page 6.2-44-45).

Birds

^LeConte's thrasher running on the ground between shrubs.

Contractors for the solar applicant found these special-status birds on the site: Western Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia hypugaea), Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus), Le Conte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei), Crissal Thrasher (Toxostoma crissale), Vaux’s Swift (Chaetura vauxi), Brewer’s Sparrow (Spizella breweri).

"Loss of nesting and foraging habitat for these special-status bird species would

adversely affect populations of these species within the Ivanpah Valley" (page 6.2-45).

<Brewer's sparrow.

The FSA/DEIS fails to mention several additional state and federal sensitive species that potentially occur on the site:

CDFG Species of Special Concern:

Mountain Plover – potential habitat. Also CA BLM sensitive species.

Northern Goshawk – migrant and summer sightings on Clark Mountain (potential breeder) (Source: Arnold Small. 1994. California Birds: Their Status and Distribution. Ibis Publishing Company: Vista, CA). Also CA BLM sensitive species.

Northern Harrier - migrant.

Long-eared Owl – migrant, wintering.

Short-eared Owl – migrant, wintering.

Black Swift – migrant.

Lucy's Warbler – migrant.

Yellow Warbler – migrant, breeds in Providence Mountains (Small 1994).

Fish and Wildlife Service - Birds of Conservation Concern:

Ferruginous Hawk – migrant, wintering.

Peregrine Falcon - migrant.

Whip-poor-will – rare breeding population on Clark Mountain (Small 1994).

Costa's Hummingbird – summer resident.

Calliope Hummingbird - migrant.

Lewis's Woodpecker - migrant.

Williamson's Sapsucker - migrant.

Willow Flycatcher - migrant.

Sage Thrasher - migrant.

Cactus Wren – permanent resident, breeder on site. Basin and Range Watch found nest on site in 2009.

<Cactus wren.

An assessment of project impacts on these species should be done.

The FSA/DEIS states that loss of nesting and foraging habitat for the special-status bird species would adversely affect populations of these species within the Ivanpah Valley. The “compensatory mitigation plan could offset the loss of habitat for these species and reduce the impact to less-than-significant” (page 6.2-45). The needs of the dozens of sensitive birds present may not be consistent with the needs of tortoise. A separate mitigation plan should be developed for sensitive bird species.

Another serious problem with this type of solar development, not present in parabolic trough plants, is the superheated beams reflected through the air over the heliostat fields onto the central receiver towers. Migrating or foraging birds have been burned to death flying through these beams.

>Daggett Solar 2 (earlier version as Solar 1) in pre-heat phase, reflected sun beams aimed away from the central receiver.

The paper AVIAN MORTALITY AT A SOLAR ENERGY POWER PLANT, by Michael D. McCrary, Robert L. McKernan, Raplh W. Schreiber, William D. Wagner, and Terry C. Sciarrotta, Journal of Field Ornithology, 57(2): 135-141 (pdf >>here), found that Solar 1 during 40 weeks of study, caused 70 bird fatalities involving 26 species, most from collisions with both heliostats and tower, but thirteen (19%) birds ( of 7 species) died from burning in the standby point. Heavily singed flight and contour feathers indicated that the birds burned to death. Six (46%) of these fatalities involved aerial foragers (swifts and swallows) which are apparently more susceptible to this form of mortality because of their feeding behavior.

Raptors potentially resident or migratory on the site that could be adversely impacted by towers:

Merlin

Merlin

American kestrel

Prairie falcon

Peregrine falcon

Northern harrier (photo right>>)

Swainson's hawk

Ferruginous hawk

Rough-legged hawk

Osprey

Bald eagle

Golden eagle

Sharp-shinned hawk

Cooper's hawk

Northern goshawk

A discussion of how negative affects of collisions and burning by towers during operation will be minimized and mitigated for raptors, migratory species, other birds, and bats flying during the day needs to be included in the FSA/DEIS.

Burrowing Owl

In addition to being a Species of Special Concern, the burrowing owl is also protected under Fish and Game Code Section 3503.5 and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

In addition to being a Species of Special Concern, the burrowing owl is also protected under Fish and Game Code Section 3503.5 and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

The FSA/DEIS states: “This species was detected on the ISEGS site during the 2008 surveys but not in 2007. Suitable habitat was identified. No owls, feathers, active burrows, pellets or whitewash were observed. The size and status of burrowing owl population at the project site is not known. The ISEGS site provides suitable foraging and breeding habitat for this species” (6.2-22). The document also explains that complete burrowing owl surveys will be conducted no less than 30 days prior to construction (6.2-119).

The FSA/DEIS fails to explain what survey methodology, if any, was used in 2007 and 2008 to detect burrowing owls and sign. Dates, times, surveyors, behavior should be inlcuded. We do not know whether burrowing owl surveys were conducted using recommended CDFG protocols (Burrowing Owl Survey Protocol and Mitigation Guidelines. 1993. Prepared by the California Burrowing Owl Consortium. www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/docs/boconsortium.pdf, accessed November 10, 2009).

Were surveys carried out during the hours around sunrise and/or sunset, or were owls detected incidental to other survey efforts? The FSA/DEIS does not provided evidence on how densely populated with burrowing owls the project site is. Apparently formal surveys will only be carried out a month before the project breaks ground, after the project is approved. The public is short-changed in this process.

The FSA/DEIS states: “The applicant has proposed mitigation measures to avoid and minimize impacts to nesting birds that have been incorporated into staff’s Conditions of Certification BIO-11 (Impact Avoidance and Best Management Practices), BIO-15 (Pre-construction Nest Surveys) and BIO-16 (Burrowing Owl Avoidance and Impact Minimization Measures)” (page 6.2-45). Compensatory habitat mitigation for tortoise is stated to be adequate to mitigate for Burrowing owl habitat loss (page 6.2-45).

But without any information on the status and population estimates of burrowing owls on the site, determining adequate mitigation will be difficult. A separate burrowing owl mitigation plan should be developed, before the project is permitted.

The FSA/DEIS states that biologists will “actively relocate all owls occupying burrows” on the construction site (6.2-119). The CDFG burrowing owl guidelines (ibid.:7) state that passive relocation should be used. The burrowing owl guidelines (ibid.:i) emphasizes “maintaining burrowing owls and their resources in place rather than minimizing impacts through displacement or owls to an alternate site.”

The guidelines (ibid.:10) also recommends that for off-site mitigation, replacement of occupied habitat with 9.75 acres of occupied habitat per pair or single owl found, or 13 acres of contiguous habitat per pair or single bird, or 19.5 acres of unoccupied habitat per pair or single bird. The FSA/DEIS has no discussion of this or whether any future plan will undertake these recommendations. This needs to be addressed. Lumping off-site tortoise mitigation with burrowing owl mitigation does not address the habitat acreage and foraging needs of the owls.

Bighorn Sheep

We found tracks and scat of Nelson bighorn sheep on a foothill ridge of the Clark Mountain Range about 3-4 miles above the ISEGS project site. A few beds were higher up. They probably come down to the few springsat the top of the fan to drink. We have seen groups of ewes and lambs in other parts of the Mojave Desert come down lower onto fans to feed. In Death Valley National Park they go below sea level on low hills and flats to nip off the seedheads of Desert gold flowers after they have dried. We have seen lone rams trying to cross highways in basins between mountain ranges as they move to new areas.

The destruction of so much potential bighorn sheep forgaing and migration corridor habitat is not adequately addressed for the Ivanpah project.

The FSA/DEIS admits: "Radio telemetry studies of bighorn sheep in various southwestern deserts, including the Mojave Desert of California, have found considerable movement of these sheep between mountain ranges.... Consequently, intermountain areas of the

desert floor that bighorn traverse between mountain ranges can be as important to the

long-term viability of populations as are the mountain ranges themselves..." (6.2-25).

Biological subcontractors to BrightSource said: "No studies are available that would confirm the presence of Nelson’s bighorn sheep in the project area. Given the proximity of the Clark Mountains, it is likely that bighorn sheep move down into the upper elevations of the Ivanpah Valley, including the ISEGS project area, to forage (CH2M Hill 2008 p. 3-7). Alluvial fans near steep rocky terrain can provide crucial foraging habitat for big horn sheep (Wehausen 2009)[reference missing]. For example, ewes at the end of gestation that need nutrients may come down from steep, rocky terrain looking for higher quality forage. They might use areas like the project site for only three weeks, but those three weeks are critical (Wehausen 2009[reference missing]). The Ivanpah Valley might also provide important movement corridors for deer and bighorn sheep (CH2M Hill 2008 p. 3-7). CDFG has noted that wildlife corridors are present through and adjacent to the ISEGS site, and have expressed concern that the project could adversely affect bighorn sheep.... However, no studies are available documenting bighorn use of the Ivanpah Valley as a migratory area" (6.2-26). (From: CH2M Hill. 2008. Supplemental Data Response Set 2D. Revised Draft Biological Assessment, pdf at www.energy.ca.gov >>here - note: the page numbers to this reference did not match any information about bighorn sheep)

The FSA/DEIS states: “To compensate for project impacts to Nelson’s bighorn sheep the project owner shall finance, construct and manage an artificial water source in the eastern part of the Clark Mountain range or in the State Line Hills outside of designated Wilderness” (6.2-130).

The FSA/DEIS fails to fully analyze impacts to bighorn, provide alternatives to avoid impacts, or provide measures to minimize impacts. For example, we do not believe building an artificial guzzler would mitigate for the potential loss of springs on the mountain slopes and bajadas due to groundwater pumping. How this mitigation will make up for the removal of bajada habitat used for feeding by bighorn sheep, as well as movement corridors between ranges. How will a guzzler offset loss of forage and habitat?

California Department of Fish and Game comments that historically Nelson's Bighorn sheep utilized the site during wet seasons when foraging in this area would have been the best.

The Society for the Conservation of Big Horn Sheep notes that a pre-construction baseline of big-horn sheep use should be established, followed by intensive monitoring during construction and follow-up post construction. They advocate a 1.5 mile buffer zone from the project border to the toe of the sloping mountain areas, to help connectivity of the local population and maintain the metapopulation dynamic at work with this sheep population. A wildlife corridor is absolutely essential for a healthy and viable population and for a healthy gene pool exchange, and that the buffer zone would establish a guideline or benchmark for any future development and additional loss of habitat. BrightSource agreed to shift the proposed ISEGS project boundaries and security fencing approximately 130 to 340 feet away from adjacent hills to provide a minor wildlife corridor. But fan habitat is still blocked.

The Society also suggested constructing a land bridge over Interstate highway 15

to alleviate the fragmentation and loss of wildlife connectivity resulting from past

highway construction and future energy development.The Energy Commission responded that this would not be appropriate mitigation for the ISEGS project because it would be mitigating for impacts resulting from highway construction rather than from this project. This suggestion could, however, be appropriately considered in a more regional forum such as the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (http://www.energy.ca.gov/33by2020/index.html) or the BLM Solar Programmatic Solar Environmental Impact Statement. We checked this link to www.energy.ca.gov and it shows a photo of Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signing a an execuitive order in 2008 and not much else.

The Society stated they are not convinced that ISEGS project water pumping will not have an adverse effect on the surrounding springs and seeps that are so precious to the resident wildlife population.

The Society stated they are not convinced that ISEGS project water pumping will not have an adverse effect on the surrounding springs and seeps that are so precious to the resident wildlife population.

Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) also occupy Clark Mountain, and we have seen deer traveling through lower-elevation fans and basin edges in creosote-Mojave yucca habitat elsewhere in the Mojave Desert.

<Mule deer doe in pinyon woodland of Clark Mountain, just a few miles above the ISEGS Ivanpah Valley site. August 2009.

Badger

<We photographed this Badger at night in a central Nevada basin.

American Badgers (Taxidea taxus) are present on the project site.

The FSA/DEIS states that the project would induce a large loss of Badger habitat and population within Ivanpah Valley. The “compensatory mitigation plan could offset the loss of habitat for this species and reduce the impact to less-than-significant” (page 6.2-46). The needs of the Badger may not be consistent with the needs of the tortoise. A separate mitigation plan should be developed for the Badger. No minimization plans are discussed.

The applicant plans to conduct Badger surveys during the desert tortoise clearance survey. If badger dens are found, each den shall be classified as inactive, potentially active, or definitely active. Inactive dens shall be excavated by hand and backfilled to prevent reuse by badgers. Potentially and definitely active dens shall be monitored by a Designated Biologist. If tracks are observed, the applicant would develop and implement a trapping and relocation plan. This plan should be developed now, for public review.

Bats

<Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) at dusk.

The FSA/DEIS mentions only three sensitive bat species that may occur in the area:

Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii), Pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus), and Long-legged myotis (Myotis volans).

A mine shaft was observed in the limestone hill immediately west of Ivanpah 3. While no direct impacts to the mine would occur from the project, BLM staff assessed the level of bat activity at the mine shaft by conducting a visual night survey on June 23, 2008. At least five bats were observed from the limestone hill, and one individual flew into and out of the mine shaft. Species identification was not possible with this type of survey.

Many other sensitive bat species potentially occur at the site, that are not discussed:

California BLM Sensitive Species:

California leaf-nosed bat (Macrotus californicus)

Spotted bat (Euderma maculatum)

Western mastiff-bat (Eumops perotis californicus)

Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes)

Small-footed Myotis (Myotis ciliolabrum)

Long-eared Myotis (Myotis evotis)

Yuma Myotis (Myotis yumanensis)

Cal. Species of Special Concern:

Big free-tailed bat (Nyctinomops macrotis)

Arizona Myotis (Myotis occultus)

Western red bat (Lasiurus blossevillii)

Western yellow bat (Lasiurus xanthinus)

An assessment of project impacts on these species should be done, with a discussion of whether any additional species-specific mitigation will be implemented to offset project impacts.

The FSA/DEIS says that to minimize risk of avian collisions with the heliostat towers, only flashing or strobe lights shall be installed on these towers. Lower facilities will also have lights that may attract bats.

California Department of Fish and Game comments that the FSA/DEIS does not discuss affects of night lighting on bats in the area. Insect swarms attracted to lights may lead to bat collisions. Monitoring of impacts to bats, including mortality found on-site, should be discussed with reduction of artificial lighting proposed as a potential.

Desert Scrub Habitats

^Diverse Mojave yucca, Buckhorn cholla, Creosote, and Bursage habitat on the middle of the project site.

BLM and the Energy Commission note that "the habitat in the project area that supports the special-status species is of particularly high quality in terms of species richness and diversity, including rich cactus and succulent diversity, creosote rings, micro-topographic diversity (upon which several of the special-status species depend), and currently contains relatively few non-native plants. Additionally, the project occurrences for some of the affected species (such as the nine-awned pappus grass) are robust in number, relative to the smaller (and potentially less viable or defensible) populations outside of the project area" (page 6.2-37).

"Past and current actions have significantly reduced and degraded the plant communities and wildlife habitat within the Ivanpah Valley, and the proposed project would substantially contribute to the loss of biological resources and genetic diversity of special-status species within the valley" (page 6.2-71).

"Clearing of vegetation will be permitted on roads, utility routes, building and parking areas, and temporary staging areas provided these are specifically documented on a

georeferenced aerial photo or shape file, showing the exact locations of soil

disturbance. BLM will consider relocating specific installations prior to the beginning of

construction but will not approve additional acreage under the current application" (page 6.2-156).

>Creosote ring in the middle of the project site. These old-growth shrubs grow outwards in a clonal circle, and many are estimated to be thousands of years old. Rings like this are numerous on the Ivanpah fan.

The FSA/DEIS states: “Mowing every few weeks for at least one or two seasons may be all that is required to suppress perennial vegetation” (6.2-33). Mowing may be carried out by hand-operated flail or rotary mowers. Tractors operated within native vegetation would be provided with low ground pressure tires (page 6.2-156).

The FSA/DEIS also states: “The vegetation would be cut with a flail type mower mounted tractor. Vegetation would be maintained at 12-18 inches in the vicinity of heliostats for the duration of the project. The applicant has not provided acreage estimates of what areas would be subject to this vegetation clearing during project construction and operation, but estimated that 412,600 cubic yards of vegetation would be cut and mulched...” (6.2-33).

We question whether all perennial plant species will simply “resprout” after mowing. Many shrub species are not adapted to stump-sprouting and may be killed by one cutting. Some species may only reproduce by seeding and could be killed by mowing. More studies should be carried out on individual species before a blanket statement is made. Habitats may be drastically changed by mowing treatments. Dead fuel from killed woody vegetation has the potential to build up under this treatment. A discussion of how fire fuels will be handled needs to be included.

The vegetation cutting will have a major impact on the Mojave Desert plant communities and associated animal species. The applicant should be required to provide acreage estimates of what areas would be subject to this vegetation clearing during project construction and operation before a decision to permit is made.

"In an attempt to assess the impacts of mowing the applicant conducted some

preliminary studies at the project site (CH2M Hill 2009g). The researchers clipped seven

species (burrobush, creosote bush, cheese bush, pencil cactus, silver cholla, Nevada

Mormon tea, and Mojave yucca) at the project site in March 2009 and evaluated them

for regrowth and vigor in April 2009. The 35 clipped plants showed vigorous resprouting

following mowing (CH2M Hill 2009g). The results of this study indicated that mowed

plants will initially respond by re-sprouting from the base, but staff does not believe that

this preliminary research provides useful information about the long-term effects of

mowing on the project area’s plant communities" (page 6.2-33).

Rare Plant Communities

Thousands of barrel cacti were found, as high as densities of 15 mature barrel cacti per acre in some localized areas. "This density is unusual because it occurs on a bajada rather than on rocky slopes where high barrel cactus densities would be expected," the FSA/DEIS notes (page 6.2-10).

<Cottontop cactus, also called Clustered barrel cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus), on the Ivanpah 1 site. The FSA/DEIS sates 3,501 of these cacti were found on the project site.

The applicant decided that no rare plant communities are present at the site. A cursory look around, however, and comparison with source material, makes us question this finding.

In A Manual of California Vegetation, second edition, by John O. Sawyer, Todd Keeler-Wolf, and Julie M. Evens, 2008, California Native Plant Society and California Department of Fish and Game, the authors say that for the Larrea tridentata-Ambrosia dumosa Shrubland Alliance (Creosote bush-white burr sage scrub): "The presence of several non-native plants, particularly Brassica tournefortii, Bromus spp., and Schismus spp., has greatly increased fire frequencies and led to the degradation and destruction of many hectares of this alliance. Long-term, intensive grazing, OHV activity, mining, and military operations have also left their mark.... We need to identify, monitor, and manage areas free of these degrading influences" (page 568).

The Ivanpah Valley fan site is just such a large intact area of creosote-bursage scrub that is relatively free of weeds, has only light (and easily reversible) grazing, almost no off-roading except on three designated tracks, and no other development disturbance. We recommend it be preserved and protected.

In addition, the authors state that such associations with Pleuraphis rigida (Big galleta grass, also named Hilaria rigida), and "those with a diverse shrub layer are G1 S1" (page 566). The G1 S1 (Global 1 State 1) status rank means the plant community is rare and has "fewer than 6 viable occurrences worldwide/statewide, and/or up to 518 hectares" (page 45). The Ivanpah site plant community has galleta grass and a diverse shrub layer (see our species list >>here), and is worthy of more studies to determine its status.

>Big galleta grass bunches in creosote-bursage shrub community with cholla and yucca. Ivanpah 2 site.

A quick check of the California Natural Diversity Database shows other rare communities that could be present on the Ivanpah site:

*33.010.07 Creosote Bush-White Ratteny-Big Galleta [Larrea tridentata-Krameria grayi-Pleuraphis rigida] (Keeler-Wolf et al. 1998).

*33.010.14 Creosote Bush - Big Galleta - Anderson’s Wolfberry [Larrea tridentata-Pleuraphis

rigida-Lycium andersonii] (Keeler-Wolf and Thomas 2000).

*33.140.17 Creosote Bush - White Bursage - Big Galleta [Larrea tridentata-Ambrosia

dumosa-Pleuraphis rigida] (Keeler-Wolf and Thomas 2000) .

33.140.33 Creosote Bush - White Bursage - Barrel Cactus [Larrea tridentata-Ambrosia

dumosa-Echinocactus polycephalus] (Keeler-Wolf and Thomas 2000)

*33.140.35 Creosote Bush - White Bursage - Cryptogrammic crust [Larrea tridentata-

Ambrosia dumosa-Cryptogrammic crust] (Keeler-Wolf and Thomas 2000).

*33.320.01 Blue Sage [Salvia dorrii] (Keeler-Wolf and Thomas 2000).

" Lead and trustee agencies may request that impacts to these communities be addressed in environmental documents" the website says. (Department of Fish and Game

Biogeographic Data Branch Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program List of California Terrestrial Natural Communities Recognized by The California Natural Diversity Database September 2003 Edition)

^Blue sage (Salvia dorrii) and Wolfberry (Lycium sp.) on the Ivanpah site, April 2009.

^Barrel cactus and Mojave yucca on the ISEGS site. The FSA/DEIS says that 2,869 barrel cacti (Ferocactus cylindraceus) were found on the project site.

Ephemeral Wash Habitats

The project area is located in the Ivanpah hydrologic unit of the South Lahontan

Watershed, which includes approximately 278,486 acres in the Ivanpah and Pahrump

Valleys of California and Nevada

"Staff concludes that the ephemeral drainages at the ISEGS project site provide

substantial hydrological and biological values and functions, including: hydrological

connections with Ivanpah Dry Lake; stream energy dissipation during high-water flows

that reduces erosion and improves water quality; surface and subsurface water storage;

groundwater recharge; sediment transport, storage, and deposition aiding in floodplain

maintenance and development; nutrient cycling; support for vegetation communities that

help stabilize stream banks and provide wildlife habitat and a movement corridor" (FSA/DEIS page 6.2-14).

^View of ephemeral washes on Ivanpah 3, from the Metamorphic Hill.

"The applicant estimates that 37.66 acres would be the total extent of impacts to the

project site’s ephemeral drainages. Staff considers this to be a substantial

underestimate of the impacts that are likely to occur to drainages during construction

and operation. Staff believes it is unlikely that disturbance associated with heliostat

installation could be feasibly limited to the footprint of a 10-foot wide maintenance path.

In addition, mowing of vegetation to a 12 – 18 inch height beneath the heliostats within

drainages during construction and operations would add considerably to the extent of

impacts. Staff further considers any drainage that is accessible to construction vehicles

to be potentially vulnerable to disturbance, unless the applicant is able to establish

fencing at all the proposed road crossings on all the ephemeral drainages and ensure

that construction traffic is limited to those crossings. After major storm events many of

the road crossings would be likely to require reconstruction, particularly on the stream

banks where soil has been disturbed as a result of grading to make ingress and egress

more level. As maintenance paths and roads develop washouts, and maintenance

workers are likely to seek wider routes to avoid rough spots, enlarging the original

footprint of the roads. Considering the vast network of paths and roads proposed in the

solar fields even small incremental widenings would amount to an ongoing degradation

of ephemeral streams. "

"Staff concludes that all 198 acres of the ephemeral drainages on the ISEGS project

area are potentially vulnerable to soil and vegetation disturbance as a result of road

building, installation of heliostats, construction of power blocks and other project

features, prolonged use of the construction logistics area, construction of linear facilities,

as well as ongoing vegetation maintenance, weed control, and other maintenance

activities associated with project operation. These drainages currently support

undisturbed native plant communities that help stabilize stream banks and provide

valuable wildlife habitat and wildlife movement corridors. Energy Commission staff

considers impacts to the project area drainages to be significant because the ISEGS

project would fragment and degrade the beneficial functions and values that these state

waters provide to wildlife. "

"Staff’s proposed Condition of Certification BIO-20 specifies that, in addition to

minimizing impacts to drainages where feasible, the applicant acquire and enhance

property that includes 198 acres of ephemeral drainages similar to those on the ISEGS

site. This mitigation could be integrated with the desert tortoise mitigation requirement

for acquisition and enhancement of suitable desert tortoise habitat. With implementation

of this proposed condition of certification impacts to the project area’s ephemeral

drainages would be reduced to less-than-significant levels" (page 6.2-63).

<Wash with Catclaw acacia (Acacia gregii), showing debris depsoited by floods.

What lands will be acquired, and where? A discussion of whether mitigation lands will be one contiguous parcel or many, should be included. Mitigation lands for ephemeral streams should be considered independently of tortoise mitigation lands.

^The strange inlfated seedpod and purple flowers of "Paperbag bush" (Salazaria mexicana), growing in washes on the upper fan.